Although Africans continued to be regarded and treated as inferior by colonial powers despite their involvement in World War 1, this did not prevent sentiments of anti colonisation from taking root, particularly in the context of Senegal and Tanzania.

When the Great War is talked about and studied it is usually depicted as something that only affected and only involved Europeans. This, however, was not the case with nearly the entire globe being implicated in the war due to colonial territories these European countries had. Countries such as Australia, India and Nepal were brought into the war as well as countries in the West Indies, Africa and the Middle East. Approximately 2.3 million African soldiers and labourers being part of World War 1. This research paper aims to shed light on the involvement of Africans, the racist ideology that pervades their involvement in the war and ultimately the ways in which their involvement contributed to their identity and stirred sentiments of decolonization.

This paper will focus on the military involvement of French West Africa particularly Senegal and Tanzania in German East Africa. Both geographical regions given context for the various capacities in which Africans were involved in the First World War. In French West Africa soldiers were mobilized to fight in Europe whereas in German East Africa, Africans were enlisted to fight against British forces in the region.

Aderinto, a historian specializing in African history, argues that African involvement in the World War was inevitable given European powers and their imperialist agenda and colonial conquest in Africa.

The question of Africans being involved in the war came with understandable resistance from colonial powers. For one Africans taking up arms was seen as something which could threaten colonial power. Page argues that there was an unwritten law of sorts early into the war that Europeans would not deploy Africans to fight against other Europeans. Germany condemned the use of non-white soldiers in the war in 1915 by lableing it as a somewhat savage act unprecedented acts of war. In 1914 only white men residing in the territory of Southern Rhodesia (present day Zimbabwe) were allowed to register for military service. There was an aversion to arm Africans which was popular even before the war as it raised questions of white superiority. When it came to the deployment of Africans however on European soil some countries were particularly against it.

In other ways Africans were doubted as being able to act accordingly in modern warfare. This initial hesitation meant that Africans were only mobilized by colonial powers such as Germany, France and Britain later in the war. Only by 1916 and 1917 were Africans enlisted for armed combat particularly to fighting in Europe. Page argues that the “chronic deficiency of labour supply ” was one of the reasons for the recruitment of Africans. When military personnel was recruited it was not in large numbers given the fears of trained Africans posing a risk to the colonial powers in the region. This was only possible due to the limited white population that could not maintain the fight on both fronts. Recruitment was based on racist ideas of different tribal groups in various colonies. Stereotypes of more “warlike” groups propagated the idea of “primal” Africans.

Just as there were reasons for European nations using Africans in war, be it as carriers or in combat, there were also reasons behind Africans choosing to enlist in the war. In French West Africa, politicians and religious leaders had to see to the recruitment of young men. These leaders in the community had further reach than the colonial forces which allowed for a more effective recruitment. This process however was often not done free willingly, with leaders often being coerced by colonial powers to assist with recruitment. Men were also incentivized with promises of the war elevating their position within society.

In German East Africa men did not join due to patriotism or allegiance to Germany but rather because it was seen like a peace time enrollment and acted as a source of employment.There was also a sense of confusion felt regarding recruitment. Some men thought they had been conscripted and therefore had no choice in the matter. Hesitation to enlist was a shared feeling in both French West Africa and German East Africa with many feeling that the war was something foreign to them, and propaganda not being as persuasive or effective as it was in Europe. In German East Africa approximately 11 000 thousand African soldiers and 3 000 German soldiers were mobilized in an effort to prevent British occupation. France on the other hand recruited over 140 000 West African soldiers throughout the war to help in defence of the Western front.

The war fought in German East Africa was known as the East African Campaign and was lead by German commander Lettow-Vorbeck. The African soldiers in German West Africa were often referred to as askari which translates to soldier in Swahili. These askaris experienced ongoing battles in this region right up until 1917 when 5 000 men were surrounded and forced to surrender to the British. Bloody battles such as the Battle of Mahiwa and Tanga resulted in high death tolls. By the end of the war over 2 000 African askaris lives had been lost on the German side whereas 10 000 lives had been lost on the British side.

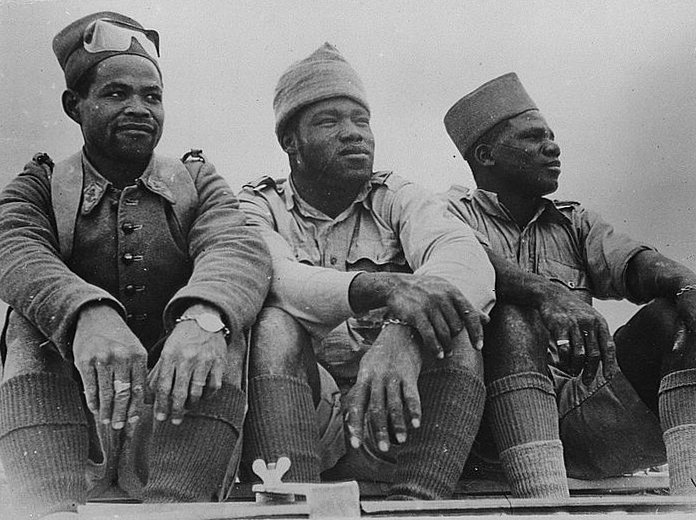

Tirailleur was the word used to describe West African soldiers fighting on behalf of French. Tirailleur translates to “skirmisher” or “riflemen” and dates back to 1857 when it was first formed. Tirailleur forces were also part of World War 2 and only disbanded in 1958. As the war progressed, the Tirailleurs were dying in their thousands. By 1917, they were deliberately used as cannon fodder explicitly to reduce French casualties. Africans were seen as disposable and of a lower value than their French counterparts.This sentiment was shared across France and likely Europe when considering the value of African soldiers.

European mobilization of African soldiers was founded in an ideology of superiority, and functioned through belittling and dehumanizing Africans. Charles Mangin who as head commander between 1907 and 1911 who argued in favour of African soldiers being recruited. He saw having African troops as necessary reserves in the event of war. He developed an analysis rooted in racism of Africans being good soldiers. There was this idea that African troops would be able to withstand the weather conditions and fighting better than their European counterparts. This ties into the idea of Africans being “primitive” and therefore more able to withstand pain and discomfort.Africans were described as coming from societies which meant they could take orders well and lastly that the vastness of Africa had served as training ground for war.

This assumption of their innate militaristic abilities was overshadowed by their inferiority, however, to Europeans and consequently made them disposable in war. The president of France, Clemence said in 1917 when the death toll was high on the warfront that he “would rather have 10 Africans die than 1 Frenchman.” Some authors argue that these racial perceptions of Africans, particularly in the case of France played into the significantly higher death rate of African troops on the Western front. He also mentions in another article how these racial perceptions were illustrated and widely known 2 decades prior during the Scramble for Africa.

This ideology of African inferiority found itself not only among the elite but was evident even in what French soldiers thought about Africans. In accounts by Leon Bocquet a soldier during the war, he describes Africans as grand enfants who act on instinct rather than reason and whom despite being loyal are in need of leadership to guide them.

This belief that African troops were in need of leadership resulted in Africans soldiers having to stand at attention even when in a higher military rank. In addition to that Africans were hindered from advancing and moving on to higher military ranks. The highest position a soldier could attain at the time was sergeant-major and despite working in the same position they would be paid significantly less than their European comrades.( 112)

Furthermore, Senegalese soldiers had segregated battalions, often only coming into contact with French soldiers for brief periods of time immediately before and after staging an attack. In addition to that training camps for Senegalese soldiers were in very isolated parts of France and in 1916 recommendations were made for segregated hospitals for Senegalse troops for further isolation. With limited interaction with French people it proved challenging for soldiers to learn French, with most of them having limited understanding of it before arriving in France. French officers made an effort to only speak to soldiers in pidgin French believing that French was too complex for Africans to understand. African soldiers unlike French soldiers were rarely allowed to take brief leaves to return home. Tirailleur were only allowed breaks in 1918 when it was France realized how low their morale was.Tirailleur made up a high percentage of combat units within the French army.

Despite the continuation of racist colonial ideology and ideas of European superiority during the first world war , the experiences of enlisted Africans served in furthering ideas of decolonization.

“Africans who served in Europe blurred colonial boundaries, as their experiences during the war reshaped their perceptions of colonialism and challenged their categorization as “colonial subjects.”

In this quotation Ginio argues that the involvement of Africans was part of shaping a new identity for African people and questioning the legitimacy of colonial rule on the continent .

Senegalese men who enlisted in the French army had benefits such as becoming French citizens and thus obtaining rights they previously would not have had. This ability to elevate one’s place in society through citizenship was appealing to many soldiers.

In French West Africa, particularly Senegal, Africans are noted as fighting very ardently against the British. The creation of an enemy is an effective way to foster a sense of shared identity. A strong sense of identity is especially important when it comes to unifying people and forming a nation. Independant nationhood although not realized until after both the first and second world war was a concept influenced by the onset of World War 1 and the enlistment of Africans.

In German and British East Africa, men from across sub-Saharan Africa were mobilized to fight during this time, often alongside each other. These interactions would have allowed for a greater understanding by Africans of the reach of European powers and just how many people were subjectugated under their control. Encounters with other Africans with shared experiences both in and outside of the context of war would have encouraged camaraderie. The first world war has linkages to decolonization movements that would become very important in the history of the continent.

The oral histories from Africans during the first world war tell of the cruel conditions and realities faced by men enlisted as well as their confusion as to why they had to fight in a war in the first case. However, despite this Africans found themselves carrying rifles and occupying positions in society that had formerly been impossible. This ability to be on somewhat equal footing with European men when it came to armed combat was completely unheard of. European men were generally seen as a superior figure, but the war complicated this narrative, with black and white soldiers fighting, getting injured and dying alongside each other for a common cause.

In conclusion, despite the racism and imperialist ideology at the heart of Africans involved in the First World War, their involvement in the war also acted as a unifying factor as it partly added to a sense of nationhood and camaraderie. It would be a mistake however to label the first world war as the starting point of awareness and decolonization. When framed in the larger context of history we are able to see the ways in which it contributed anti-colonial movements, in ways that although subtle cannot and should not be ignored.

Bibliography

- Page, Melvin E.“Africa and the First World War”.ed. 2014. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Weller, Patrick.“Reflection on World War I, Hypocrisy and David Olusoga’s The World’s War: Forgotten Soldiers of Empire.” Social Alternatives 37 (3, 2018): 47–49.https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,shib&db=a9h&AN=133646742&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

- Moyd, Michelle.“Color Lines, Front Lines: The First World War from the South.” Radical History Review 2018 (131, 2018): 13. doi:10.1215/01636545-4355109.

- Lunn, Joe H. “‘Bons Soldats’ and ‘sales Nègres’: Changing French Perceptions of West African Soldiers during the First World War.” French Colonial History 1 (2002): 1-16. www.jstor.org/stable/41938103.

- Lunn, Joe. “‘Les Races Guerrierès’: Racial Preconceptions in the French Military about West African Soldiers during the First World War.” Journal of Contemporary History 34, no. 4 (1999): 517-36. www.jstor.org/stable/261249.

- Olusoga, David: “Black soldiers were expendable– then forgettable”, The Guardian. 11 Nov 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/nov/11/david-olusoga-black-soldiers-first-world-war-expendable

- Paice, Edward. “World War I: The African Front.” First Pegasus Books Trade Paperback ed. New York: Pegasus Books, 2010.

- Ginio, R.“The French Army and Its African Soldiers : The Years of Decolonization”. Lincoln, NB: University of Nebraska Press (2017).

- Ramaswamy, Chitra. “The Unremembered: Britain’s Forgotten War Heroes review – David Lammy condemns a shameful history – Politician examines the fate of African soldiers who fought in the first world war, finding decay, disregard, and denial.” Guardian, The (London, England), November 10, 2019: 14. NewsBank: Access World News. https://infoweb-newsbank-com.eu1.proxy.openathens.net/apps/news/document-view?p=AWNB&docref=news/17722C83FB462DD8.

- Samson, Anne. “World War I in Africa: The Forgotten Conflict among the European Powers.” Paperback ed. International Library of Twentieth Century History, 50. London: I.B. Tauris, 2019.

- Strachan, Hew. “The First World War in Africa”. Reprint 2007 ed. The First World War. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Liebau, H. The World in World Wars : Experiences, Perceptions and Perspectives From Africa and Asia. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill,(2010).

- Killingray, David. 2001. “African Voices from Two World Wars.” Historical Research 74 (186): 425. doi:10.1111/1468-2281.00136.